Introduction

This series explores how the recent censorship episodes at

Goodreads and booksellers in England represent symptoms of the larger

upheavals roiling the publishing world. In particular I am looking at how

they each relate to what I will call ‘emerging genres,’ genres whose

standards and conventions, critical reception, distribution and a host

of other aspects are being actively negotiated and contested by a

community of “stakeholders”: authors, fans, reviewers, critics,

publishers, etc. Since I am both a writer and heavy reader of erotica

and its subgenre, M/M romance, I will use those as my primary lens for

analyzing the implications of these scandals.

As I said in my first piece, erotica’s

connection to the British scandal is self-evident. The connection to

Goodreads is less direct, but I think in the end more important. There

is nothing unexpected that booksellers stung by criticism that they sell

pornography would react impulsively by attempting to purge it from

their shelves. The Goodreads episode was not concerned with erotica at

all, and superficially the types of material censored seem quite narrow

in scope, but in fact its implications for those who care about erotica

or any emerging genre are far more sinister, and unlike the British

scandal there was nothing inevitable about it.

Controversy at Goodreads

With longstanding, ugly quarrels it can be very difficult for outsiders to get past the

he said/she

said aspects. The conflict that spawned this debacle is polarized enough by now that any pretense to

impartiality is impossible, and I am not going to spend time arguing "my

side." Though I have had no role whatsoever in this quarrel, I do think

the reviewers have the right of it. (For those interested in immersing

themselves in the details, I refer you to an excellent series of posts

on the blog

Soapboxing as well as the book

Off-Topic, discussed below.)

For

the purposes of my own argument, it is enough to know that a very

vitriolic conflict between authors and readers over negative reviews

mostly of YA books has been escalating for more than a year, drawing

negative press and the kind of attention social networking sites most

fear.

It is not chance that this conflict erupted over

YA, which along with erotica is one of the genres that has been most

popular with self-publishing authors. One of the fundamental facts of

life for those of us who self-publish is that reader reviews and

word-of-mouth are everything.

Now authors getting a wee

verklempt about bad reviews is nothing new (though brownies help—as do tequila shots). What is new is how crucial

reader

reviews are to sales, and how visible they are. The moment a Goodreads

review is posted, it is accessible worldwide by the site's 20 million

users. As if that weren't enough, booksellers like Kobo (and now Amazon

on certain Kindles) also post Goodreads reviews on the book page

for buyers to see.

Goodreads'

Author Guidelines strongly

warn authors never to respond to negative reviews, but authors don’t

always realize or don’t care, and some have gone after “bully” reviewers for

sabotaging their careers, even resorting to tactics like "doxing,"

tracking down and posting real names and addresses for hostile

adversaries to see. Readers on Goodreads began keeping track of these authors and

slapping with the “Badly Behaving Author” label, which can be very

damaging since the tag tends to go viral on the site, and many Goodreads

users make a point of never buying any book by a BBA.

Goodreads' Response

Given

the publicity and acrimony surrounding these fights and their threat to

the reputation and actual functioning of Goodreads, it was not

surprising that the site’s management felt they had to intervene—which

they did on September 20 with the following announcement:

[Goodreads

will] Delete content focused on author behavior. We have had a policy

of removing reviews that were created primarily to talk about author

behavior from the community book page. Once removed, these reviews would

remain on the member’s profile. Starting today, we will now delete

these entirely from the site. We will also delete shelves and lists of

books on Goodreads that are focused on author behavior.

There

are a lot of reasons this was a problem. The policy itself as worded is

nonsensical. As people have pointed out, does the prohibition on

discussing “author behavior” apply to reviews of

Mein Kampf? Does

their insistence that "books should stand on their own merit" mean we

cannot discuss Orson Scott Card’s very public anti-gay statements when

reviewing

Ender’s Game? (For an excellent survey of how banning discussion of author behavior "

ignores all of postmodern literary criticism," see Emma Sea's

Why Goodreads New Review Rules Are Censorship.)

Far more baffling was that Goodreads would come down

so decidedly on the authors’ side, when according to their own

guidelines any author involved in a conflict with a reviewer is

de facto

guilty of inappropriate conduct. Because management has said nothing

about their thinking, users have been left to fear the worst: that the

decision represents the first stage in a larger shift by Goodreads,

which is now owned by Amazon, away from reviewing and the free exchange

of ideas towards a bottom-line prioritizing of selling books and

advertising.

Whether those fears are grounded or not,

it simply staggers that a site devoted to book

lovers could conclude that the best way to quell rancor and controversy

was through censorship of one side. It is no surprise that the result

was an explosion of anger and protests that has drawn in users who would

never be at risk of having a shelf or review deleted, and risks yet

more attention from the media. And here’s where I’d like to back up my

claim in the

previous essay on how management’s decision represents a serious failure to understand the mentality of the site’s users.

A Community of Stakeholders

As

far as the economics of publishing today goes, there are two crucial

types of reader: the first is the old-style consumer whose book

purchases are based on the best-seller lists or recommendations by

mass-media organs of varying degrees of prestige. It is no stretch to

say that these buyers pay the salaries of traditional establishment

publishing.

Then there is our second type of reader,

the one who is driving the new publishing paradigm. This reader is a

passionate and voracious consumer of an emerging genre dominated by

self- and indie publishing. Because there are no professional reviews,

and often no agents, editors, or publishers to decide on a book’s

merits, that role falls to the readers. Many of them read 100, 200, 500

books a year in their genre. They are not just fans, but taste-makers,

and ultimately authorities—because there aren’t any others. Most heavy

readers of erotica and M/M fall into this category—as do many of

Goodreads’ most active reviewers.

When you first join

Goodreads, the site appears to work like Facebook—indeed, it invites you

again and again to duplicate your FB friend list on the site. That

suggests the creators conceived of it as a place for actual, real-world

friends to exchange book recs and post the occasional review. And for

our first type of reader, that is probably all that is needed or wanted.

But for the second type of reader, Goodreads serves

as the primary meeting place for what I earlier termed the stakeholders

of an emerging genre. To take a conspicuous example, the

M/M Romance reader group,

one of the largest on the site with more than 12,000 members, justly

advertises itself as “The #1 resource on the web for M/M fiction.”

Beyond providing dozens of fora for readers to talk books or meet

authors, the group also organizes innovative publishing events including

an incredibly popular one where readers suggest a story line which any

author is free to take up. Readers get hundreds of free stories that

they had a hand in creating, while authors get exposure, a chance to

experiment, and the good will of the community. The M/M group organizers

are powerful players in their own right, and work tirelessly along with

bloggers, authors, and readers to help develop this genre.

For

these users, Goodreads is infinitely more than

Facebook-with-books-instead-of-pictures-of-the-kids. It is a

professional and creative space, and the key meeting place for their

community. For them, the autocratic and boneheaded nature of

management’s decision is deeply disturbing, especially in the light of

Amazon’s acquisition of the site. Management’s move seems geared towards

casting users more in the passive role of our first type of reader. It

is not paranoid to say that this familiar type of reader is infinitely

preferred by the traditional publishing establishment. It is the second

type who is revolutionizing the industry, rendering obsolete all the old

axioms on who matters, what succeeds, and how you make money.

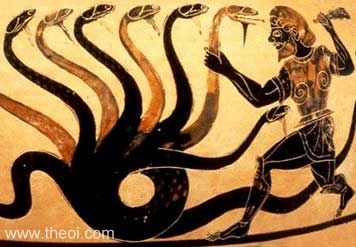

The Part with the Tentacles

Goodreads

has itself in part to thank that this second type of reader has found

her voice. After the site’s managers announced the new policy on

September 20, users immediately organized protests, dubbed hydra

reviews, which went viral. When those were censored, the protesters put

together a collection of essays,

Off Topic: The Story of an Internet Revolt,

which was published on November 3 with no restrictions on distribution.

In the four days since it went live, hundreds of users have shelved or

reviewed the book, and a write-in campaign has started to nominate the

book for the Goodreads Choice Award.

Whether this new

reader will continue to find a home on Goodreads is impossible to know.

What is clear is that she will never again be satisfied with the role of

passive consumer of other people’s taste.